If Taiwan doesn’t come immediately to mind when you think of tea, it’s understandable but unfortunate. Overshadowed by its neighbor China, the motherland of tea, as well as nearby Japan, another tea powerhouse, it’s easy to see how Taiwan does not get all the due respect it deserves when it comes to tea. We’re about to help you see why widespread respect for Taiwan teas is oolong overdue.

Taiwan is one of the most densely populated places in the world, with over 23 million people. The vast majority of them live in the urban areas in the plains portion of Taiwan, which accounts for roughly one-third of the island. The capital, Taipei, is a bustling major global city with a stunning skyline featuring Taipei 101, a 101-story building that for a time was the world’s tallest building. The mountains seen in Taipei’s background represent the remaining two-thirds of the island, along with lush forests.

Image: Taipei 101, one of the world’s tallest buildings

It’s in those mountainous areas of Taiwan that the magic of some of the world’s finest oolong teas takes place.

How Taiwan Became a Major Oolong Producer

Oolongs likely first appeared within the last three to four hundred years in China’s Fujian province. Eventually, as the tea became more popular and widespread, oolong makers from Fujian also began immigrating to Taiwan. Taiwan lies directly across the Taiwan Strait from Fujian, and most of its residents speak the same Fujian dialect of Chinese. Today, the best oolongs still come from China and Taiwan.

Then Taiwan got its big break. When China was under embargo during the 1950s and 1960s, Taiwanese tea makers took the opportunity to make their fortunes producing ersatz versions of Lung Ching, Gunpowder, Ti Guan Yin and other mainland Chinese tea classics. When the embargo was lifted, cheaper and better versions suddenly became available from China itself. The Taiwanese were forced to grow something else. Luckily for us, they chose to grow oolongs. Capitalizing on the benefits of vacuum packaging and air shipping, they did away with the heavy firings once required to preserve and transport teas, creating oolongs of terrific lightness and nuance. They achieved such success that in just the last several years, a growing number of private mainland Chinese tea makers have copied them, lightening and improving their oolongs in turn. As a result, today we have some of the freshest, most remarkable oolongs ever available.

Image: Oolong tea plantation in Taiwan

A Quick Look at What Makes an Oolong an Oolong

Oolongs bridge the divide between green and black teas. The process that turns teas black is called “oxidation.” Suffice to say, if green teas are not oxidized at all, and black teas are 100 percent oxidized, oolongs range from 10 to 75 percent. Because of their singular methods of production, oolongs take on an astonishing array of flavors and aromas. Many oolongs are creamy, their liquor literally coating your mouth like fresh cream. Others are almost effervescent, practically fizzing like Champagne. Their variety of colors is lovely to behold, from the pale greenish-yellow liquor of Ti Guan Yin to the dark orange brew of Fenghuang ShuiXian.

Image: Tea leaves drying at a tea factory in Taiwan

Unlike most teas, oolongs can actually improve with multiple brewings. Both the Chinese and the Taiwanese like to drink oolongs gong fu style, brewing the tea in several rounds, using a small clay pot, then pouring the tea out into tiny ceramic cups and sipping it with six or seven friends. To brew an oolong gong fu style, fill a small teapot (4-6 fl. oz) with about 1½ to 2 tablespoons of tea. Rinse the leaves with lukewarm water, then brew them for one minute. Pour out the tea into small cups, then start a fresh pot with the same leaves while you drink the first round. Brew each subsequent pot for an additional 30 seconds. The flavors and aromas will continue to evolve through five to seven rounds before fading.

Here at Harney, we love the complexities and unique qualities of oolongs, and we’re always excited to share some of the world’s best with our customers. Here are some of the Taiwan oolong teas we offer.

Wenshan Baozhong. One of the oldest Taiwanese oolongs, the Taiwanese say BaoZhong is their most aromatic oolong. The tea is so fragrant, it is hard to stop smelling its blend of gardenia, jasmine, and butter aromas. At its freshest, Baozhong tastes of nothing but honeyed flowers. After a few brews, it loses some of that sheen and takes on a lovely seriousness. If the tea is more than a few months old, it begins to taste like a vegetal green tea.

Making a trip to the hometown of this tea is a highlight of any trip to Taiwan. Ping-Lin is truly a tea town with tea restaurants, one of the world’s largest tea museums, statues of the hardworking pluckers, even streetlights that resemble teapots. It is set in a beautiful nature preserve in a quiet mountainside spot just outside Taipei that is loaded with gardenia flowers.

Ping-Lin restaurants serve wonderful foods cooked in BaoZhong tea: pork belly braised in it, fresh trout poached in it, even tea puddings sweetened with BaoZhong and condensed milk. Before you cook with it, get to know its delicate floral flavors. They are some of the most refined in the world of oolongs.

Ali San Oolong. A balled oolong, Ali San is among the creamiest of oolongs, with a nice sensation and some butteriness along with lime citrus notes and a quiet, underlying vegetal flavor.

This was one of the first of the high mountain teas, from the Ali Shan area in the southern mountains of Taiwan. The tea is named for this steep five-thousand-foot peak. About 20 years ago, Taiwan’s tea industry went through a radical change; they stopped producing the old teas that were exported to Westerners, and these better oolongs were made for the newly prosperous domestic market.

Li Shan. Considered to be among the best oolong teas in the world, Li Shan comes from one of Taiwan’s highest mountain areas, in the same region as Ali Shan. The tea plants must battle cold (sometimes even snow) and frequent mists. This makes a rare and haunting brew, with echoes of honey and cream.

Li Shan is one of the most recent high mountain (gao shan) tea growing areas. It is located in the middle of Taiwan’s central mountain region. The tea is rolled into balls using special machines. In the old days, they used the feet of strong teamen to bend the leaf. It has a sweet aroma and a creamy, lemon- and pear-like flavor with underlying vegetal notes.

Da Yu Lin. Another high mountain gao shan oolong, this smooth and creamy tea is made near the more famous Li Shan area. Enjoy its lemon and sugar cane aroma and lemon curd-like flavor.

Dong Ding Light. While we were not able to find a traditional Dong Ding tea that we liked in 2020 – a challenging year to source tea, among other difficulties last year brought – we are pleased to offer this lightly roasted oolong, made in the mountains in the middle of Taiwan. It has a creamy taste, like lemon taffy, with underlying vegetal notes and a sweet aroma that is a mixture of gardenia and lemons.

Tea makers have cultivated Dong Ding around the town of Luku in the foothills of Taiwan’s central mountain range since the mid-1800s. They adopted the production methods of their cousins in southern Fujian Province and roll the large tea leaves into a ball. This traditional style is oxidized for a shorter time than other Dong Dings.

Made almost like Ali Shan, Dong Ding is a lovely example of a creamy, lemony oolong, slightly darker than its high-mountain brethren and slightly more restrained. Along with Wenshan BaoZhong, Dong Ding is Taiwan’s most famous and beloved oolong and most likely its first.

Whether Dong Ding came before Wenshan BaoZhong is a matter of some debate. Legend has it a tea maker from Fujian province in China made the short hop across the Taiwan Strait along with a dozen tea bushes, planting them at the base of Dong Ding Mountain. Tea makers quickly adopted the rolled-ball method used in Ti Guan Yin.

While Dong Ding is grown within view of the snow-peaked Dong Ding Mountain (hence its name), the tea is not considered a high-mountain oolong because of the mountain’s lower elevation. Nonetheless, over the last 20 years, Dong Ding makers have begun imitating the high-altitude tea-making techniques, making their tea much lighter than they once did, oxidizing and firing the leaves for much shorter times. As a result, today’s Dong Ding now resembles Ali Shan and Li Shan, but with a darker liquor and similar but more subdued floral and citrus flavors.

Formosa Oolong. Formosa oolong is the style of brown oolong that generations of Americans have loved, especially for its toasty flavor. Don’t worry about the stems, the tea is traditionally made this way in Taiwan. It is oxidized to about 75%, so it is darker than most other oolongs. It has a nutty aroma with toasty notes and a subtle sweet peach and roasted carrots covered by toasted walnut flavor.

In the 15th century when they first came upon the island, the Portuguese named Taiwan Formosa, or “beautiful island.” In the tea world, Formosa and Taiwan remain interchangeable, just like Ceylon and Sri Lanka. Formosa oolong tea was invented in the mid-19th century by a British entrepreneur named John Dodd. If they speak no other English, Taiwanese tea men can pronounce the name “John Dodd” flawlessly. They consider Dodd a national hero for first bringing the island’s teas to the world stage.

In 1865, Dodd saw that the world tea market was about to change dramatically. China supplied almost all the tea in the world. What Dodd knew (and the Chinese did not) was that the British were preparing, on a mass scale, to grow their own Indian tea. Dodd shrewdly came up with a tea that he thought might compete with both the Chinese and Indian alternatives. Working in Taiwan, he developed and marketed a dark oolong under the name “Formosa Oolong.” The tea traveled well yet was lighter, fruiter, and more flavorful than the heavily fired black teas then on the market. Formosa became such a hit in both Europe and the United States that it remained one of the world’s favorite teas well into the 20th century. Its popularity grew both in the U.S. and in Great Britain until the Japanese occupation of Taiwan all but ended production. After World War II, U.S. and British demand increased again, but after China reopened in the 1970s, demand fell off because of superior teas available from both China and Taiwan.

Brisk, nutty, and somewhat fruity, Formosa oolong offers a history lesson as much as it helps cultivate your oolong palate. The tea was once considered the Champagne of teas and the standard for oolongs in the U.S. In the last two decades, other lighter and more aromatic oolongs have outpaced it so that today it is made by only a handful of Taiwanese tea makers. My father included Formosa oolong among the half dozen teas he sold when he first entered the tea business in 1970. Now we have to order it custom-made. We use it mostly as a base in our Earl Grey tea and other blends that call for a mild, dark oolong.

Image: Visiting tea harvesters during our travels to tea plantations in Taiwan

As you can see, the Taiwanese have given us much more to celebrate than bubble tea! We encourage you to try a variety of Taiwan oolongs to gain an appreciation for their differences and artistry. If you’d like to picture yourself sipping a cuppa while enjoying the view from the 101st floor of Taipei 101 or at a table in a picturesque Ping-Lin tea restaurant, we encourage that, too!

1 comment

Randi T Marshall

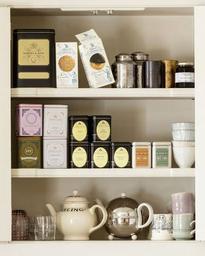

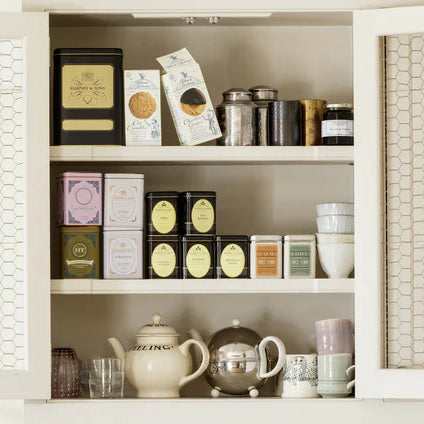

Thank you so much for these articles. It’s wonderful to read about the history of tea. I also love some of the Taiwan oolongs. I have a variety in my cabinet.

Thank you so much for these articles. It’s wonderful to read about the history of tea. I also love some of the Taiwan oolongs. I have a variety in my cabinet.