The journey tea takes before it lands in your cup is quite an interesting one, and it certainly doesn’t begin in our plant in Millerton, New York. Rather, as you know, it begins as a plant but it’s certainly not as easy as grow tea, harvest tea, bag tea, ship tea, brew tea. So we thought we’d boil down the process, if you will, and explain it in a two-part series. Part 1 will focus on growing, harvesting and withering.

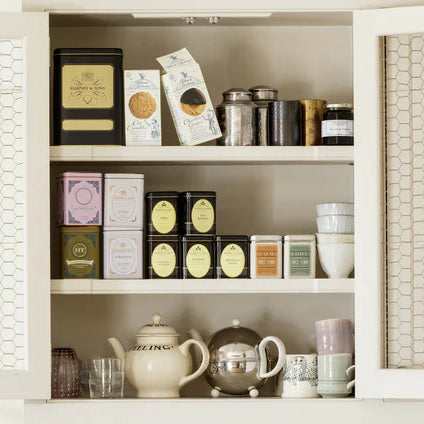

To cultivate a taste for tea, it helps to understand the stages of tea production since each stage contributes to the final taste. Much of the information that follows comes from my dad’s book, The Harney & Sons Guide to Tea, which I highly recommend if you’d truly like to become a student of tea. I also recommend it because he’s my dad.

Let’s get started!

Growing

While the transformation of tea from bitter, waxy leaves on a bush to liquor in a pot may seem absurdly magical, tea makers actually follow the same basic steps worked out by farmers in China by the 18th century. The tea plant, part of the Camellia genus, comes in three main varieties that are used in the production of tea: sinensis, assamica and cambodiensis.

Tea starts its life as bright green leaves on a branch of the evergreen Camellia sinensis. These trees can grow to heights of 30 feet or more; they thrive in dappled shade in most subtropical climates. The white and pink blossoms yield edible (if bitter) small tea nuts. The soft, shiny leaves have finely jagged edges and slightly pointed tips. Fresh-plucked tea leaves make an incredibly bitter brew; only after they have withered and dried do they take on their extraordinary aromas and flavors.

The Camellia sinensis var. sinensis is a sturdy plant that has greater resistance to cold and drought than other varieties, so it is often grown at high altitudes as well as in regions with difficult climates. “Sinensis” means “from China,” the country where tea was first discovered. This native Chinese variety of the tea plant is native to China’s Yunnan province and also thrives in the mountains of northeastern India’s Darjeeling region.

Meanwhile, in the nearby province of Assam, botanists discovered an entirely separate variety of tea plant, a larger-leafed variety they called Camellia sinensis var. assamica. Vast plantations quickly grew up in that flatter and more low-lying region, churning out immense quantities of assamica’s larger leaves. In the wild, some trees can grow to a height of 90 feet and live for many centuries, but in a tea plantation, they generally live no longer than 50 years.

Finally, the properties of Camellia sinensis var. cambodiensis are not as appreciated as the sinensis and assamica varieties, so it is rarely used for tea cultivation. It is, however, excellent for use in hybridization and is sometimes used to create new cultivars.

As you can see, not all tea plants are the same and therefore there are many variables in play when it comes to growing tea. Soil, climate, altitude, latitude and other conditions are huge factors in growing tea. The same tea plant can even produce different-tasting tea depending on where and how it is grown. In general, however, tea plants need lots of rain and, depending on the plant type, tend to grow best in tropical or subtropical regions, while some thrive in steep mountain ranges where the altitude and climate help the plants develop higher concentrations of aromatic oils that create more richly flavored teas. While generally hardy and adaptable, they are not fond of wintery conditions (which is one reason we don’t grow tea in upstate New York!). That said, tea plants do benefit from climatic variations, which can help develop flavors. The stress caused by weather changes disturbs the chloroplasts in the leaves and triggers a reaction from the plant, which strives to retain chlorophyll in its leaves, improving the flavor of the tea. More on that in a bit!

Harvesting

As we mentioned, flavor begins in the fields. Scientists have identified over 600 flavors and aromas in tea, many with obscure and wonderful names like “linalool” and “hexanol.” The miracle is that tea makers create these hundreds of flavors from only six classes of chemical compounds that all reside within the tea plant: color pigments, sugars, amino acids, fatty acids, caffeine and polyphenols. These compounds exist in nature to nourish and protect the plant against attack. The aromas and flavors we find so enticing in tea actually deter aphids, leafhoppers and other insects from eating the leaves. In essence, tea makers pose as insects, damaging the leaves to provoke them to defend themselves -- and, in the process, rendering them delicious.

The first secret to flavorful tea is to gather the leaves at their peak, when they contain these compounds in the most mouthwatering proportions. With the exception of tropical teas from Assam and Ceylon, the finest teas peak in the spring. [Our blog on tea seasons will give you further insight into this topic.]

Like all plants, tea bushes grow through photosynthesis. The color pigments chlorophyll and carotene absorb sunlight so that the plant can convert carbon dioxide and water into glucose and other sugars. When the sun fades in the winter, the bushes go dormant, storing nutrients in their roots. As the winter dormancy ends and the temperature warms, the plants draw on these nutrients to create more leaves. The plant forges amino acids to build proteins. And it produces caffeine and polyphenols to repel bugs and protect the plant from attack. The two chemicals appear to disorient herbivores, dissuading them from eating the leaves.

For tea connoisseurs, caffeine and polyphenols each affect a tea’s flavor along with sugars, amino acids and fatty acids. Sugars obviously make the tea sweet. Fatty acids provide tea with many of its aromas. Amino acids influence body, giving teas their relative brothiness, or umami. One amino acid in particular, called “L-theanine” (“theanine” for short), seems to create the most mouth-filling qualities. Japanese tea makers frequently speak of the favorable theanine levels in their best teas. Theanine has also been increasingly studied for its ability to soothe the brain and enhance concentration, making tea a gentler stimulant than coffee. Caffeine, an alkaloid, gives tea a mildly bitter bite. Polyphenols furnish tea with its tannic qualities, its relative astringency or briskness. Two have a particularly strong effect: EGCG, or epigallocatechin-3-gallate, a smooth-tasting polyphenol; and EC, or epicatechin, a harsher, grassy-tasting molecule. Spring teas taste particularly well rounded and mellow because they have the most EGCG and the least EC. Spring teas have different names in different countries: Qing Ming teas in China, Senchas in Japan, First Flush teas in Darjeeling.

In summer, the plants slow their growth, digging in for the heat and the assault of late-season insects. Japanese Banchas plucked in May and June taste grassy and thin compared with early spring Senchas because they have about a third fewer amino acids and a much higher proportion of EC to EGCG. Second Flush Darjeelings and later-season oolongs like Bai Hao have far less glucose and fewer amino acids than their earlier-season equivalents. Makers of both teas compensate for the nutrient loss by allowing insects to attack them before harvesting. The plant reacts by producing a defensive compound with a lovely fruity aroma evocative of Muscat grapes.

To ensure the most flavors, tea makers have also developed a dizzying number of tea varietals, each with differing levels of the six chemical compounds. By breeding Camellia sinensis var. sinensis with Camellia sinensis var. assamica, tea makers have developed hundreds of cultivars. The exquisite Chinese breed Da Bai (big white”) produces extra-large, glucose-packed buds, perfect for white teas and tippy black teas. The Japanese cultivar yabukita grows in 90 percent of that country’s tea gardens, because of its above-average levels of amino acids and relatively low levels of polyphenols. The black teas Keemun (China) and New Vithanakande (Sri Lanka) both get their chocolate flavors in part from cultivars with extra amino acids.

After choosing the tea cultivar and the timing of the harvest, tea makers can also control the levels of compounds in tea -- and therefore the tea’s flavor -- by gathering the leaves by hand. The finest teas also come from the very youngest leaves. Tea plants grow by sending out buds -- incipient leaves shaped like spears that unfurl into young leaves, then mature. The youngest leaves on the plant are called “leafsets,” consisting of a bud and its adjoining two leaves. These leafsets are loaded with nutrients to feed and protect the sprouts as they grow. Fully mature leaves contain comparatively few nutrients, since they send whatever they photosynthesize into the roots for storage. Mechanical harvesters cannot distinguish between leafsets and mature leaves; like crude hedge clippers, they merely shear the bushes of their outer layer. As a result, machine-harvested teas often taste dull and insipid. Harvesting by hand is meticulous work. Harvesters often wear gloves affixed with razor blades to snip off the leafsets one at a time, their fingers flying from branch to branch as they work their way down the bushes, gently storing the cut leaves in straw hampers as they work.

Withering

For all the work involved in harvesting it, freshly plucked tea tastes like bitter grass. Its hundreds of flavors don’t begin to emerge until tea makers go to work to draw them out. These flavors exist in the plant to defend it against attack. The first line of defense emerges right after the leaves have been plucked. Cut off from the roots, the leaves begin to lose moisture and nutrients. In an effort to feed themselves, the leaves break down starches into glucose and proteins into amino acids. In what scientists believe is an attempt to alert the rest of the plant that they are in distress, the leaves also transform fatty acids into aromatic compounds. These alerts are the first flavors to emerge, in this process called “withering,” or dehydration, as tea makers let the leaves go limp.

The longer the leaves wither, the more aromas the final tea yields. Green teas wither only over the short trip between the field and the factory, just long enough to generate some of the lemony, grassy scientist of linalools and hexanols. Oolongs and black teas wither much longer. Assam CTC teas are among the least aromatic black teas, as they wither very briefly; the humidity of tropical Assam makes dehydration nearly impossible.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, high-mountain oolongs, First Flush Darjeelings and some high-grown Ceylons wither for several hours more -- not just to provoke the aromas, but also to dry out the leaves and concentrate the compounds. Over so much time, fatty acids continue to degrade into yet more aromatic compounds like the geranium-scented geraniol and jasmine-scented methyl jasmonate. The aromatic compound methyl salicylate gives Uva Highlands Ceylon black tea its remarkable minty aroma. In addition to fatty acid degradation, in black teas and darker oolongs, which continue to wither as they oxidize, the pigment carotene starts to degrade into the aromatic compounds ionones, damascones and damascenones, forming delicious fruity aromas reminiscent of apricots, peaches and honey.

The scent of withering tea is incomparable -- fresh and floral, far more vibrant than the final scents of brewed tea. Like a tea man’s perfume counter, tea factories at the peak of harvest throb with aromas of lemon, jasmine and apricot. They are a joy to walk through.

Hopefully, you find all this science as fascinating as we do! As you can see, Mother Nature has a lot to do with how that tea in your cuppa tastes -- but there’s more to come! Stay tuned for From Tree to Tea, Part 2 where we’ll talk about fixing, rolling, oxidation, fermentation, firing and sorting. Until then: cheers!

2 comments

Brad

A trip to the UK whilst sick made me gravitate to nurse tea constantly, this Louisiana boy became a BIG tea convert! I’ve done such a deep dive into the beautiful rabbit hole of tea, and reading this blog post made me feel like such a neophyte tea nerd!! I felt my eyes sting at the beauty and depth of all of this!! Wow! I’ve become a fast Harney & Sons devotee and it’s driving my family crazy! Ha! Thank you so much for this!

A trip to the UK whilst sick made me gravitate to nurse tea constantly, this Louisiana boy became a BIG tea convert! I’ve done such a deep dive into the beautiful rabbit hole of tea, and reading this blog post made me feel like such a neophyte tea nerd!! I felt my eyes sting at the beauty and depth of all of this!! Wow! I’ve become a fast Harney & Sons devotee and it’s driving my family crazy! Ha! Thank you so much for this!

Philip

Fascinating…the things that Mother Nature/God provides for our enjoyment. Thanx for posting this, looking forward to pt 2!!!

Fascinating…the things that Mother Nature/God provides for our enjoyment. Thanx for posting this, looking forward to pt 2!!!